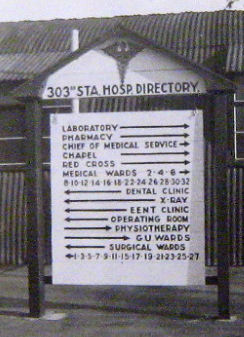

WWII American Air Force Hospital (in Lilford Park)

Brief History of the Hospital

Aerial view of the hospital

The 303rd Station Hospital was a WWII hospital established by the American Airforce in the grounds of Lilford Park at Lilford Hall in September 1943 as a 750 bed hospital to provide medical attention to wounded men returning from combat at Molesworth Air Base (303rd Bombardment Group H). The Hospital also catered for illness and accidents of Molesworth Base personnel, and wounded men returning from combat at Polebrook Air Base (351st BG) and Grafton Underwood Air Base (384th BG), and wounded from Continental Europe after D-day.

The Hospital was expanded to a 1,500 bed hospital after D-day. The original Commanding Officer was Major Thompson followed by Colonels Smith, Abramson and Ragan. Seventy-five nurses had accommodation at Lilford Hall itself. The hospital was disbanded in May 1945.

In particular,the Hospital served the 8000+ men and women who served in the 303rd Bombardment Group (H) "Hell's Angels" during World War II. The 303rd Bomb Group was an Eighth Air Force, B-17 Bomber Group stationed at Molesworth, England from 1942 to 1945.

Detailed History of the Hospital

In the spring of 1943, Major Thomas Thompson, an orthopedic surgeon at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, began recruiting personnel for an overseas medical unit. In July, 1943, the 303rd Station Hospital was formed at Camp McCall, North Carolina. Major Thompson was the original Commanding Officer of the unit.

1st Lt Florine Thompson was assigned as Chief Nurse, 2nd Lt Gladys Gillilaud, Head Nurse of the Enlisted Men's Orthopedic Ward, and 2nd Lt Frances Nunn, Head Nurse of the Officer's Orthopedic Ward. Personnel at Walter Reed received orders on 10 July 1943 to report to the 303rd Station Hospital at Camp McCall. Additional female personnel assigned were a dietitian, physical therapist, and three Red Cross Workers.

The entire enlisted and male officers personnel was then assigned to the unit at Camp McCall. During July and August they were engaged in overseas training including the infiltration course and the obstacle course. These exercises included the female personnel, and included gas mask drills, many lectures and required swimming. During this training period Major Thompson left the unit. Lt Col. Smith was assigned as commanding officer of the unit.

On the 23rd of August 1943, the 303rd Station Hospital including thirty-nine male officers, five female officers, three Red Cross workers and 392 enlisted men were ordered "To proceed from Camp McCall to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, to arrive no later than 1600, 31st August 1943. This is a permanent change of station, movement by motor and/or rail." The entire unit less the advanced party left Camp McCall by troop train.

At Camp Kilmer they were joined by seventy-two 2nd Lt. Army Nurses. Twenty-two came from Camp Campbell, Ky, twenty-five from Camp Atterbury, Indiana, and twenty-five from Fort Knox, Ky.

The nurses exchanged their white duty uniforms for tan and white seersucker field uniforms and caps. Their Class A uniforms were exchanged for O.D. issues. They were issued a set of fatigues and field equipment including gas masks, mess kits and canteens.

They all left to embark on the "Empress of Russia," which was a Canadian cruise ship, and left New York Harbor on 5 Sept. 1943, but had to return to port because they could not keep up with the convoy of troop ships. Finally on Sept. 8th-9th, they sailed again as part of a convoy of ships loaded with war supplies. They were in the middle of the convoy and sailed the northern route and were on board a total of twenty-one days.

They all left to embark on the "Empress of Russia," which was a Canadian cruise ship, and left New York Harbor on 5 Sept. 1943, but had to return to port because they could not keep up with the convoy of troop ships. Finally on Sept. 8th-9th, they sailed again as part of a convoy of ships loaded with war supplies. They were in the middle of the convoy and sailed the northern route and were on board a total of twenty-one days.

There was much fog on the trip and a constant zig-zagging to avoid the threat of submarines.

They finally landed in the Firth of Clyde at Glasgow, Scotland, where we were met by a bag-pipe brigade as they disembarked and a contingent of volunteers serving tea in their new canteen cups.

These 500+ medical personnel then traveled by train from Glasgow to Peterborough, and then to Thrapston, England, where they were met by Ambulances that took them to the 303rd Station Hospital location in Lilford Park, close to Molesworth Air Base were 303rd Bombardment Group was based.The first night they slept in the hospital wards. The next morning, the nurses were taken to Lilford Hall where the nurses were quartered for the next two years.

Lord Lilford lived in one wing of the "castle" and was reported to have said he would just as soon have a Nazi bomb hit the "castle" as seventy-five American Army nurses. There was cold running water in the castle and an abolition hut in the rear for bathing. Their first test of survival was to keep the fireplace burning as there was no central heating.

Their first task in organizing the hospital wards was to standardize them. The medicine cabinets, linen closets, kitchens, etc. were all set up the same so that nursing personnel could easily adjust from one ward to another. They were also standardized so that they could work with torches, if it became necessary. Nursing personnel worked twelve hour shifts -- 7 a.m. - 7 p.m. and 7 p.m. - 7 a.m. with two hours off during the shift if possible. There was an occasional 48 hour V.O.C.O.

Their first task in organizing the hospital wards was to standardize them. The medicine cabinets, linen closets, kitchens, etc. were all set up the same so that nursing personnel could easily adjust from one ward to another. They were also standardized so that they could work with torches, if it became necessary. Nursing personnel worked twelve hour shifts -- 7 a.m. - 7 p.m. and 7 p.m. - 7 a.m. with two hours off during the shift if possible. There was an occasional 48 hour V.O.C.O.

They were originally designated as the 303rd Station Hospital with a 750 bed capacity. After D-Day the hospital expanded to 1500 beds. This was done by erecting fifteen bed tents attached to the nissen hut wards.

The hospital had as many as three hundred patients arrive at one time. The rail-head was Thrapston, where ambulances lined up to transport the patients. There were many patients with shrapnel wounds and many with frozen feet.

Col. Smith left the unit as Commanding Officer during 1943, and Col. Ira Abrahamson was assigned as Commanding Officer following Col. Smith. Col. Abrahamson was replaced by Col. Tillman A. Ragan who remained with the unit until They were broken up in the spring of 1945.

The 303rd Station Hospital served the medical needs of thousands of servicemen until it was closed in the spring of 1945.

Some of the nurses were transferred to the 230th General Hospital for transfer to the Pacific Theatre. Following cessation of hostilities in the Pacific some of the nurses were assigned to various units for the Army of occupation or for transfer to the U.S.A.

While the personnel at the Hospital were not stationed at Molesworth Air Base, they were a supporting organization that played a big part in the success of the 303rd Bomb Group, as well as the other allied forces in the area. They are honored as a Support Organization on the 303rd Bomb Group Memorial, near the main gate of RAF Molesworth. The 303rd Bomb Group was fortunate to have such a top-notch medical facility virtually next door.

Wartime press article on Lilford Hospital

A transcription of Page 6 of the Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph, February 23, 1944 about the hospital in Lilford Park follows:

Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph

Established October 4, 1897 - Wednesday, February 23, 1944 - Price Three Halfpence

U.S. FLIERS’ HOSPITAL IN NORTHANTS

'Evening Telegraph' Visit to the Transformed Lilford Estate

Recently we published an article describing an “Evening Telegraph” reporter’s visit to a United States Army Air Force bomber station in this country. Here is another “Evening Telegraph” reporter’s impression of a U.S. Army Station Hospital at Lilford Hall in Northamptonshire, which serves troops of all types throughout the area.

Recently we published an article describing an “Evening Telegraph” reporter’s visit to a United States Army Air Force bomber station in this country. Here is another “Evening Telegraph” reporter’s impression of a U.S. Army Station Hospital at Lilford Hall in Northamptonshire, which serves troops of all types throughout the area.

Often though it is that Flying Fortress make daylight raids on enemy territory, and we think of the men of the U.S.A.A.F. on their long and hazardous journeys yet little do we hear of that side of the effort of the United Nations which helps to maintain flying personnel and other of the Forces in health and efficiency.

To-day, through the kind co-operation of the Public Relations Officer (Chief Warrant Officer M. D. Goldenberg), I had the privilege of visiting the scene of a transformation which would be unbelievable in peace-time; the parkland attached to an ancient mansion now being occupied by innumerable huts which constituted a first-rate hospital, living accommodation for medical officers and men.

British “Aloofness”

|

“The countryside is very beautiful–we do not have the fine hedges that you have here,” he remarked when asked his opinion of England. “You do not have the socialibility that we have,” he went on, “but that is explained by the English tradition of every man’s home being his castle.”

“At first we thought the English were sort of aloof,” he observed “but when we understood their love and pride in their homes, it changed our whole attitude; and we got a better appreciation of the people.”

Himself the embodiment of geniality, and that “bedside manner” which is essential to create confidence with patients, the Colonel (who also served in the last war) then gave a comprehensive picture of the layout of the hospital buildings, as indicated on plans. In an atmosphere of cool and calculated efficiency, it was an interesting revelation to hear him remark that, in emergency cases, they did not let the making of records of in-coming patients interfere with attention to their immediate needs.

Medical Library

It was obvious that good use was being made of the extensive grounds, now intersected with well-made pathways, which would shortly be covered overhead for the benefit of the patients.

The library being mentioned, it was learned that in addition of having the finest hospital equipment that was available, they had from all parts of the world the fruits of the latest research and of surgical and medical experience, particularly from the Russian theatre of war. In addition, the staff frequently had consultation with men from other hospitals. Also, whilst they sent their men to English hospitals to gain new ideas, so the English sent theirs to the American units, and at the present time a famous plastic surgeon of this country was touring American hospitals while a famous surgeon of America was giving lectures to British medical officers.

“There is a very fine relationship which exists in the medical profession and it is something by which we all benefit,” remarked the commanding officer, “and there is no doubt that it will be continued after the war.”

Dental Service

|

In addition to extractions and such-like dentistry, there are mechanics and the equipment and material for the making of false teeth. Those concerned in this work feel they are doing a particularly valuable service as it helps to get the air personnel quickly back on to operations. Airmen cannot go on missions when their artificial teeth are broken because they cannot control the oxygen tube. If the dentists had to send away for a replacement, the airmen would be three weeks away from sorties, but through going to this hospital the artificial teeth they require are completed in about two days so that they are back in the air without delay. Also in the case of a jaw fracture, the dental staff can make a splint in one day.

Best or Better

“Everything is as in civilian life at its best, and perhaps better,” said the officer in charge, and he mentioned that among recent “customers” was a commanding officer of a bomber wing who traveled 100 miles to be treated.

Patients have included R.A.F. officers, Fighting French and Polish men, whilst emergency cases sometimes include civilian employees at the hospital. Painless extractions were truly painless, it was asserted, and it was mentioned that an improved type of local anesthetic was in use, containing an organic substance that replaced adrenalin, which sometimes was the cause of a type of nausea in the past.

Adjacent was the X-ray dental room, where the last word in X-ray cameras was engaged in photographing a section of the jaw of a member of the U.S.A.A.F.

“He has trouble with a tooth at high altitudes,” explained the X-ray operator, “and I think it is a large filling in the tooth which is probably causing the trouble; so we are taking the photograph to confirm, or otherwise, our suspicions.”

Care of Eyes

Our reporter next visited the eye, ear, nose and throat clinic. Here, at his request, he went through some of the tests ordinarily given fighter pilots. Lieut. Jennings, in charge of this work, demonstrated, in addition, several of the instruments he uses in diagnosing systemic disease from the appearance of the inner coats of the eye.

Captain Schoolman, chief of the ear, nose and throat department was in the act of treating patients with sinus disease by modern methods.

Most comprehensive was the survey given by Major Needham B. Bateman, chief of the surgical service. He went to great pains to show the various departments, commencing with the operating theatre, where was standing an English-made sterilizer that was kindly loaned until their own American machine arrived.

Those patients able to enjoy recreation were found to be having a happy time at a film show, or enjoying themselves at the Red Cross Club of which the secretary is Miss Lybie Pintner. Several were working with leather making wallets suitable for carrying pound notes, since the American dollar is smaller in size, and the men found the wallets they had were inadequate. Many things, as explained by Miss Miriam Follmer, who is in charge of recreation work, are also made of plaster, glass from damaged bombers, and salvaged tin cans.

To add to the patients’ pleasure there was a radio-gram, snooker and table tennis tables, and a library, a special place being reserved for newspapers from hometowns. Tournaments and social parties were held every week, as revealed by the program on the notice board of the week’s activities. Beside the work attached to this side of the organization, the Red Cross volunteers also help by writing letters home for those men with fractures or hand injuries, and running all kinds of errands for them.

In the “Castle”

|

Thus fittingly concluded the tour of the large-scale array of buildings and the efficient hospital service behind the “front line,” the value of which, to the fighting forces, is inestimable.

Finally, please click here for more photographs of the American WW II Hospital.