The Formal Gardens at Lilford Hall

.jpg)

History of the Formal Gardens.

The important gardens at Lilford Hall are separate and distinct from the house, and are known as the Formal Gardens as well as the pleasure grounds, and provide a setting of formal walks and patterned beds of flowers. Beyond the counter-slope of the Park lies the enclosed and separate area known as The Walled Gardens.

The 250 years old Formal Gardens were started by the prominent architect Henry Flitcroft between 1750 and 1770 in the eastern part of the Park, at the same time as when the village of Lillford and Lilford Church were removed to form the Parkland. The Formal Gardens are shown on an estate map dated 1791, with The Walled Garden particularly delineated at that time, together with garden areas to the south and west of The Walled Garden.

The Formal Gardens now comprise The Walled Garden (also known as The Green Walk), The Broad Walk (also known as The Yew Walk), The Children's Garden, and The Rock Garden (also known as The Rockery), which are arranged adjacent to each other and cover an area of around five acres.

During the late 1800's and early 1900's the Formal Gardens were enlarged by Lady Milly Louisa Isabella Powys (nee Soltau-Symons) wife of John Powys (born 1863 died 1945) the 5th Baron Lilford. Her proudest day came when Queen Mary (wife of King George V of England) visited the Formal Gardens at Lilford.

Country Life article

The Gardens at Lilford are considered of major importance, as will be seen from a five page Country Life article about the gardens which was published in 1900:

“It is at the Formal Gardens, not at the house, that the pleasures of the garden must be sought as a place to wander in and see the beauty of trees and flowers. Here are the flowers and the old walls, the shady lawns, the yew walks, and the natural flowering trees. Broad acres of lawn, masses of flowering trees, especially lilacs and hawthorns, form the outer zone. The lilacs in spring are wonderful. They form the centre of every clump or grow in masses alone. The air is heavy with their perfume, and the ancient may trees seem covered with showers of lightly-fallen snow, so thick is the blossom.

“It is at the Formal Gardens, not at the house, that the pleasures of the garden must be sought as a place to wander in and see the beauty of trees and flowers. Here are the flowers and the old walls, the shady lawns, the yew walks, and the natural flowering trees. Broad acres of lawn, masses of flowering trees, especially lilacs and hawthorns, form the outer zone. The lilacs in spring are wonderful. They form the centre of every clump or grow in masses alone. The air is heavy with their perfume, and the ancient may trees seem covered with showers of lightly-fallen snow, so thick is the blossom.

Here are small pools, overhung with oaks and walnuts, and covered with wild-fowl waiting to be fed. Cast in a handful of grain, and the surface is violently agitated by the downward rush of the diving duck, which plunge below the surface at the moment when the food sinks, while the others remain to consume what floats upon the top.

To the centre of this wild pleasaunce, where the flowers have their kingdom and assured dominion, the architect and the landscape gardener have added the charms of grey stone walls and terraces, steps and colonnades, and walls of close-clipped yews, the halfway step between the appearance and reality of garden architecture.

The Walled Garden, with its pears hanging against the grey stone, its deep green walk and lines of herbaceous border, backed by espalier fruit trees, owes its main beauty, like most walled gardens, to its walks.

By the sides of these the back-ground which is used in the somewhat similar garden at Helmingham Hall in Suffolk, with excellent effect, might well be employed to give more colour. At Helmingham a background to the herbaceous border is formed by masses of clematis, and sweet peas are trained on tall wire netting, thus completely screening the interior of the rectangle into which the garden is divided, within which the necessary, but not always ornamental, vegetables for the house are planted.

The Walled Garden at Lilford joins two other gardens of special use and purpose. One of these gardens is The Children's Garden. It is an ideal child’s garden, with a nice summer-house thatched with reed, its own cherry tree and pear tree, old stone walls, and a dear little fountain, just the place for imaginative children to be happy in and make believe all kinds of delightful adventures and triumphs of planting flowers and harvests of fruits from their own trees.

The Walled Garden at Lilford joins two other gardens of special use and purpose. One of these gardens is The Children's Garden. It is an ideal child’s garden, with a nice summer-house thatched with reed, its own cherry tree and pear tree, old stone walls, and a dear little fountain, just the place for imaginative children to be happy in and make believe all kinds of delightful adventures and triumphs of planting flowers and harvests of fruits from their own trees.

Close by is a pond, which contains a feature not common in garden. It is inhabited by a tame and friendly otter. A former otter which lived there was so completely domesticated that it would follow the falconer wherever he went and catch fish for him. It was caught when a blind kitten, and brought up with a bottle. When it grew up it became so tame that when let loose among a crowd it would find its master by scent as quick as a dog would under the same difficulties.

Parallel with The Walled Garden runs The Yew Walk, leading to the rose garden. The approach, between dark walls of yew, makes the bright roses springing up their arches, look rosier still. Vines climb up the inner wall, variegated ivies of many sorts creep upon the terrace parapet.

The rose garden itself is, like all good rose gardens, devoted mainly to green turf and the varied offspring of the queen of flowers, except that against the dark yew hedges are masses of sunflowers and Michaelmas daisies. The roses grow on a ring of light arches surrounding a fountain.

The rose garden itself is, like all good rose gardens, devoted mainly to green turf and the varied offspring of the queen of flowers, except that against the dark yew hedges are masses of sunflowers and Michaelmas daisies. The roses grow on a ring of light arches surrounding a fountain.

This is a natural rose country, and no one would credit the fact that thirty years ago (1870) this rosary was an orchard. Crimson Rambler, Duke of Edinburgh, and many tea roses grow luxuriantly. In the outer zone of these pleasure grounds the houses of the birds, exquisitely kept, abutting on smooth lawns, and inhabited by creatures whose form and movement are alike beautiful, give a fresh note of interest.

Birds and gardens seem made for one another; and in this garden the notes of the chough and the call of the cranes mingle with the cooing of the wood-pigeons and the song of the native birds.

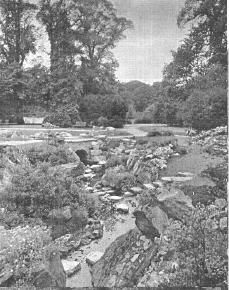

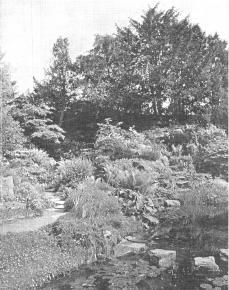

The present year (1899) has seen the permanent addition to the pleasure grounds of The Rock Garden. It was developed from an old-fashioned fernery, by letting in light and air, using the water which trickled from the old rock- work to form pools, and by adding rock-work suitable for the mountains plants to grow either side.

Thus it combines effectively the charm both of the rock and water garden, while each group of stonework, though falling into the general scheme, makes a separate little territory with its own flowers and plant life. To watch the growth of every individual plant is half the charm of these sub-Alpine gardens.

Their care is the light side of floriculture. It realises equally the dream of child gardeners and the ideals of past masters of the art. There is no end to the solicitude it claims for single plants, and those often of the minute and star-like order, tiny floral constellations on their firmament of stone.

The Rock Garden is a thing of beauty. In the pools flowering rush blossoms, and on the surface water-lilies, red, pink, yellow, and white. The water flows quite naturally from the rocks into the pools, which are set round the trees, tall water grass, and rushes.

On the rocks red Portulacas, with blossom as brilliant as pomegranate, Dianthus (Napoleon III), and others of that family flourish exceedingly. Among the most effective in groups or large patches of growth are Androsace lanuginose and A. sarmentosa, Primula rosea, and of gentians acaulis and verna.

Hardy cyclamens occupy shady corners, and many campanulas and veronicas, especially rupestris, which delights in draping rocks, give soft colour. But for genuine brilliant hues the Dianthus (Napoleon III) and Atkinsoni have few equals. In the bog garden which fringes the pools Cypripedium spectabile, pubescens, parviflorum, and Trillium grandiflorum did well.

Of the flowering shrubs cistus of sorts, Rhododendron ferrugineum and Daphne Cneorum have flourished exceedingly. Out of some 400 varieties growing in this miniature valley of rocks, many are uncommon and some really rare. Among these are Erigeron Trimorphia and E. trifidus, Saxifraga squarrosa, Pentstemon Halli, Campanula Raineri, Globularia nana alba, Petrocalllis pyrenaica, and many others.

Of the flowering shrubs cistus of sorts, Rhododendron ferrugineum and Daphne Cneorum have flourished exceedingly. Out of some 400 varieties growing in this miniature valley of rocks, many are uncommon and some really rare. Among these are Erigeron Trimorphia and E. trifidus, Saxifraga squarrosa, Pentstemon Halli, Campanula Raineri, Globularia nana alba, Petrocalllis pyrenaica, and many others.

Edelweiss grows as if native to the soil, Alpine antirrhinum and its relations, with scarlet thyme and white thyme, Alpine wallflowers, and Genista praecox, campanulas, white heather, and glacier birch have so covered the rocks with stars, bells, globes, cups, tufts, balls, and pendants formed by the hundred bright flowers of the moor and mountain that the fancy can scarcely distinguish the individual plants blended in the whole.

The most recent addition is the escallonia from the West Country, Lady Lilford being anxious to add one of her country’s choice shrubs to the growth of The Rock Garden. Before long the flowering shrubs will boast the addition of all the newest varieties of lilac; at least twelve kinds of new and improved lilacs have now joined the number of these ancient and established favourites in the pleasure grounds, where they flourish so luxuriantly.”