Darwin and Ornithological links to Lilford Hall

.jpg)

The bird link to Lilford Hall started in the late 1840's due to the life passion of the 4th Baron Lilford, namely ornithology.

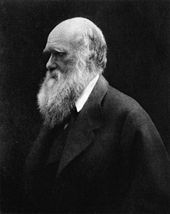

The famous aviaries at Lilford were built in the 1890's by the 4th Baron Lilford, who by this time was a distinguished ornithologist. Baron Lilford corresponded with Charles Darwin, and was even mentioned in the famous book "The Descent of Man".

At an early age Lord Lilford manifested a love for animals; at Harrow he kept a small menagerie, and also began contributing to The Zoologist. He kept a larger menagerie at Oxford, and all his spare time, during vacations and subsequently through life, as far as his health would permit, was devoted to travel for the purpose of studying animals, especially birds. During a visit to the Isles of Scilly, Wales, and Ireland, he become acquainted with Edward Clough Newcome, the best falconer of his day, and shortly afterwards took up falconry himself. His aviaries at Lilford Hall were the envy of field ornithologists, and especially noted for the collection of birds of prey. His aviaries featured birds from around the globe, including rheas, kiwis, Pink-headed Ducks and even a pair of free-flying Lammergeiers. He was responsible for the introduction of the Little Owl into England in the 1880s.

He wrote extensively about birds. In addition to some two dozen papers on ornithological subjects, contributed to the Ibis (of which he was a generous supporter), the Proceedings of the Zoological Society, and other scientific journals, he was author of: Coloured Figures of the Birds of the British Islands, in seven volumes (1885–97), which was completed by Osbert Salvin after his death, and included a biography by the zoologist Alfred Newton, and Notes on the Birds of Northamptonshire and Neighbourhood (1895). Other books include Lord Lilford on Birds (1903) edited by Auryin Trevor-Batlye. His sister Caroline Mary Drewitt (nee Powys) also wrote a book "Lord Lilford Thomas Littleton, Fourth Baron A memoir by his sister" (1900) about his life.

Baron Lilford corresponded regularly with Charles Darwin, and indeed he is even mentioned in Darwin's famous book "The Descent of Man", where in Chapter XIV on birds, Darwin writes "When birds gaze at themselves in a looking-glass (of which many instances have been recorded) we cannot feel sure that it is not from jealousy of a supposed rival, though this is not the conclusion of some observers. In other cases it is difficult to distinguish between mere curiosity and admiration. It is perhaps the former feeling which, as stated by Lord Lilford, attracts the ruff towards any bright object, so that, in the Ionian Islands, "it will dart down to a bright-coloured handkerchief, regardless of repeated shots." The common lark is drawn down from the sky, and is caught in large numbers, by a small mirror made to move and glitter in the sun. Is it admiration or curiosity which leads the magpie, raven, and some other birds to steal and secrete bright objects, such as silver articles or jewels?"

Baron Lilford corresponded regularly with Charles Darwin, and indeed he is even mentioned in Darwin's famous book "The Descent of Man", where in Chapter XIV on birds, Darwin writes "When birds gaze at themselves in a looking-glass (of which many instances have been recorded) we cannot feel sure that it is not from jealousy of a supposed rival, though this is not the conclusion of some observers. In other cases it is difficult to distinguish between mere curiosity and admiration. It is perhaps the former feeling which, as stated by Lord Lilford, attracts the ruff towards any bright object, so that, in the Ionian Islands, "it will dart down to a bright-coloured handkerchief, regardless of repeated shots." The common lark is drawn down from the sky, and is caught in large numbers, by a small mirror made to move and glitter in the sun. Is it admiration or curiosity which leads the magpie, raven, and some other birds to steal and secrete bright objects, such as silver articles or jewels?" "The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands, is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species. [In] the Galapagos Archipelago... almost every product of the land and water bears the unmistakable stamp of the American continent. There are twenty-six land birds, and twenty-five of these are ranked by Mr. Gould as distinct species, supposed to have been created here; yet the close affinity of most of these birds to American species in every character, in their habits, gestures, and tones of voice, was manifest.... The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, yet feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? Why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galapagos Archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plain a stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height or climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which resembles closely the conditions of the South American coast: in fact there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in climate, height, and size of the islands, between the Galapagos and Cape de Verde Archipelagos: but what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape de Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galapagos to America. I believe this grand fact can receive no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation; whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galapagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists, whether by occasional means of transport or by formerly continuous land, from America; and the Cape de Verde Islands from Africa; and that such colonists would be liable to modification;—the principle of inheritance still betraying their original birthplace."

"The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands, is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species. [In] the Galapagos Archipelago... almost every product of the land and water bears the unmistakable stamp of the American continent. There are twenty-six land birds, and twenty-five of these are ranked by Mr. Gould as distinct species, supposed to have been created here; yet the close affinity of most of these birds to American species in every character, in their habits, gestures, and tones of voice, was manifest.... The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, yet feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? Why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galapagos Archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plain a stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height or climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which resembles closely the conditions of the South American coast: in fact there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in climate, height, and size of the islands, between the Galapagos and Cape de Verde Archipelagos: but what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape de Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galapagos to America. I believe this grand fact can receive no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation; whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galapagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists, whether by occasional means of transport or by formerly continuous land, from America; and the Cape de Verde Islands from Africa; and that such colonists would be liable to modification;—the principle of inheritance still betraying their original birthplace."